A quarter of a century ago, on the internet nobody knew you were a dog. Now they don’t know if you’re a fridge pretending to be a dog. Pretty soon they won’t know if you’re a North Korean bot pretending to be a Japanese fridge pretending to be an American dog. We don’t seem to be making much progress on identity in what the noted media theorist Marshall McLuhan called the “new electric world”. If anything, we’re going backwards.

In a world of fake identities and fake news, where it is your nanny cam and your newsfeed getting hacked not your credit card, we need to accept that trying to digitise identity hasn’t worked and we need to start creating a new kind of identity for the new digital age instead. We need to stop trying to import those analogue identity models, rooted in Industrial Age bureaucratic hacks to deal with urban anonymity and develop notions of identity for a digital age that are more like those that McLuhan foresaw.

He founded his concepts of identity in relationships and said (a long time before the web and social media even existed) that in the coming always-on interconnected world where “everybody is involved with everybody”, that “identity cards, the old means of finding out who am I, will not work”. I’m not sure if anybody could have imagined the implications of what he was saying at the time. Yet he was absolutely correct, which is why our efforts since to take those old notions of identity and try to create online analogues have left us with an identity crisis of data breaches, hacking and lost passwords that is a considerable friction holding back the evolution of the online world.

We need a new mechanism to help people, things and bots to recognise each other. But that recognition is only the beginning, because it is the relationships that are key. Over time, that data that accrues around relationships forms a reputation (much harder to counterfeit than an identity) that will become the cornerstone of online life and the basis for interaction between people, things and bots. You can see the genesis of the online reputation economy in Uber and Airbnb, in eBay and the app store. Translate that into everyday life: In my Twitter feed, I only want to see items posted by real people with a reputation above 100. In my house, I want the alarm system to recognise only members of my family and their cars. I will give my financial services bot permission to talk to registered financial institutions on my behalf, but only those institutions with a +1 reputation amongst my friends. And so forth.

(When it comes to “intimacy”, I will only share my data with organisations that I have a relationship with and that I am sure will practice appropriate “hygiene”. I can easily imagine the data equivalent of STD notifications, where if I leak your data you make me contact everyone I had a relationship with to warn them!)

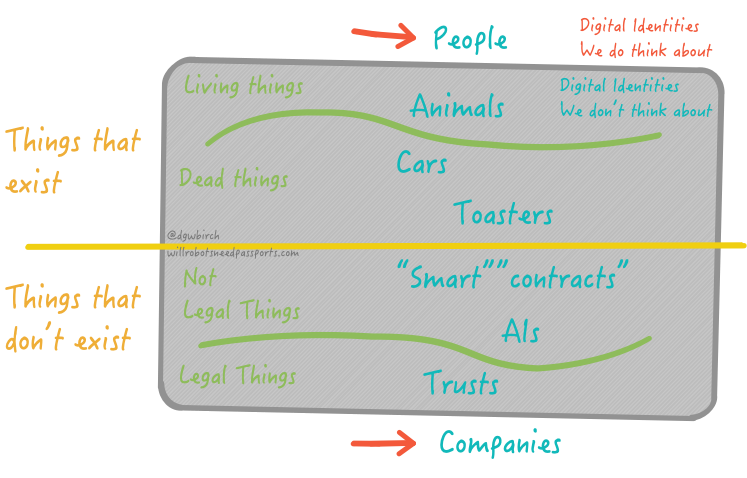

To exist in this new world of recognition, relationships and reputations, we need some form of digital identity. We need this digital identity to be universal. We don’t want one identity system for people that doesn’t interoperate with the other identity system for things, and we certainly don’t want an identity system for bots that can’t talk to people. We want an identity system that all of them can use, so that I can safely delegate the ability to open my garage door to my car in a way that I simply cannot at the moment.

How could this work? Well, in the real world, we use documents such as passports to recognise who people are and we look at visas stamped into the passport to see where they are allowed to go. The same should be true in the digital world: when a bot comes up to my house’s border control, it should have to present a passport just as a delivery driver who wants access to my shed will. These passports are not paper and pictures, of course, they are built from cryptographic keys held in tamper-resistant memory and pointers to transaction data on quantum-resistant shared ledgers, but you get the point. They may not tell anyone who you are, because they want to provide privacy as well as security, but they will tell people what you are: an employee of this company (WORKS_FOR_DHL), old enough to drink (IS_OVER_18) and in possession of a permit to drive (HAS_VALID_LICENCE).

This is not a technical manual to teach someone how to write computer software about identity. This is an attempt to build an overarching narrative about identity in the digital age, a narrative that I hope will bring together policy makers, regulators, entrepreneurs and technologists to form and deliver the identity we need for our new digital world. It is a book about what that digital identity is, how it solves real problems and how we can get there from here. “There” being the near future where robots and everything else will have passports because they have identities, relationships and reputations.

What robots won’t have, of course, is the one crucial stamp in their passports that we will have in ours: IS_A_PERSON. To advertisers, to journalists, to voters, to shopkeepers and to others, that credential will be essential prerequisite for the most important transactions. The central thrust of this narrative is that, in time, IS_A_PERSON will become the most valuable credential of all.

David G.W. Birch

March 2020.